Modus Operandi

COMMISSAIRE : MATTHIEU POIRIER

La Galerie Mitterrand est heureuse de présenter une rétrospective de l’artiste espagnol Francisco Sobrino dans les deux espaces de la galerie. Cette exposition intitulée Modus Operandi et qui se tiendra du 5 mai au 8 juillet, est réalisée sous le commissariat de Matthieu Poirier. En 2015, un Musée Francisco Sobrino a ouvert ses portes à Guadalajara (Espagne), ville dont est originaire l’artiste.

Texte de Matthieu Poirier :

Francisco Sobrino (1932-2014) fut un représentant historique du cinétisme, notamment dans le cadre du Groupe de recherche d’art visuel (G.R.A.V.), dont il fut un des fondateurs à Paris en 1960. Dès 1958, il instaure un mode opératoire radical, systématique et minimaliste qui s’inspire tant des avant-gardes historiques (constructivisme, Bauhaus, Dada, néo-plasticisme) que des sciences cognitives (psychologie de la forme, théorie de l’information, phénoménologie de la perception). Son vocabulaire visuel se réduit dès lors aux « bonnes formes », c’est-à-dire les plus simples et donc les plus immédiatement accessibles à la perception, à une poignée de valeurs colorées, le plus souvent les primaires et une seule à la fois - vers la monochromie - ou celles des matériaux bruts qu’il traite en stricts aplats, excluant toute trace de réalisation manuelle. Son projet, mené de front jusqu’en 1968 avec ses comparses du G.R.A.V., Julio Le Parc, Joël Stein, François Morellet, Horacio Garcia-Rossi et Yvaral, récuse la passivité de l’œuvre et la composition abstraite, celle liée aux courants lyriques et informels mais aussi celle liée à l’art concret, célébré au Salon des Réalités nouvelles ou encore celle pratiquée par Auguste Herbin ou Max Bill.

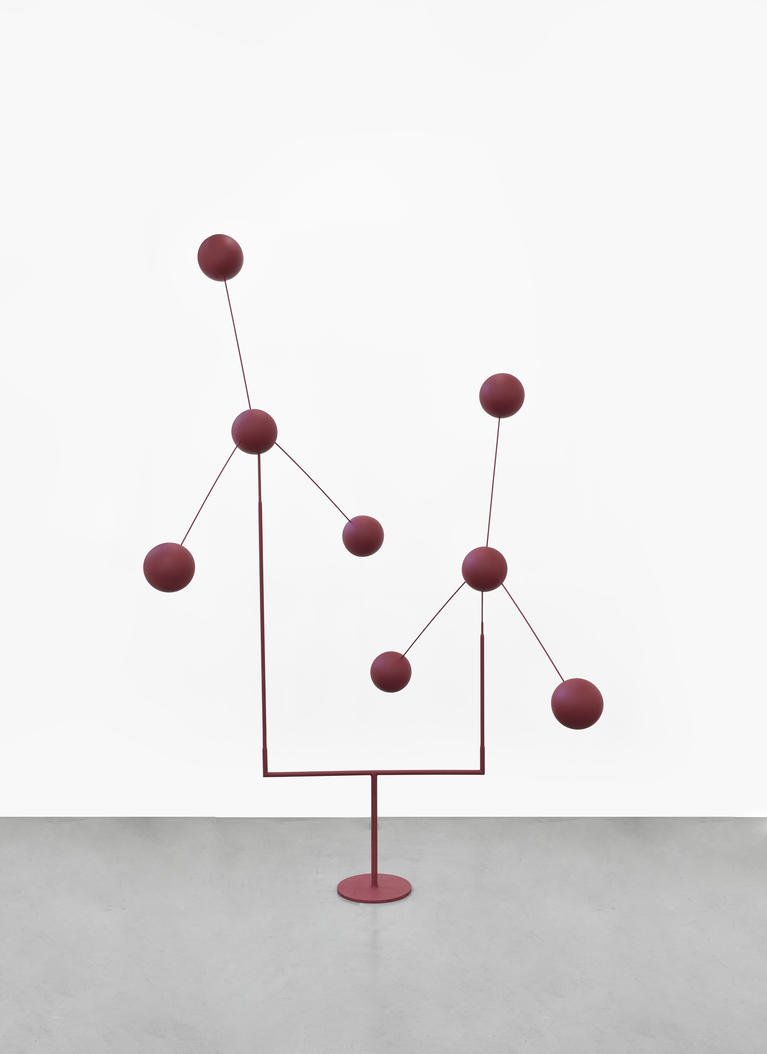

Il s’agit pour Sobrino de réformer l’art abstrait, au motif que sa composition, fut-elle « enlevée », fait toujours, in fine, du tableau ou de la sculpture un objet inerte, voire lénifiant, sur un plan sensoriel ou spatial. Ainsi, du tableau à la sculpture, les œuvres de Sobrino peuvent avoir une apparence étonnamment complexe dans le temps et l’espace, une qualité à proprement parler « relationnelle », tant ces structures ouvertes, participatives et même, parfois, pénétrables résonnent avec leur environnement immédiat, construit ou humain. Outre les structures kaléidoscopiques et rythmiques qui ont fait le succès de l’artiste, certaines torsions hélicoïdales sont surprenantes : elles donnent au régime incroyablement épuré de Sobrino une consonance baroque, rappelant même les fameuses colonnes torsadées du baldaquin créé par le Bernin pour la Basilique Saint-Pierre de Rome. Toutefois, quelle que soit leur complexité visuelle, les œuvres de Sobrino découlent toujours de procédés basiques : rotation, inversion, suite, grille, battement et autres articulations, qui se sont substitués à tout mode d’agencement traditionnel.

Cette logique rigoureuse et anti-picturale voire anti-artistique, associée aux mouvements ZERO et Nouvelle Tendance, préfigure de nombreuses réalisations associées au minimalisme nord-américain, comme par exemple les tableaux aux structures linéaires et post-painterly de Frank Stella, les parallélépipèdes déployés dans l’espace de Robert Morris, la facture industrielle et "déréalisante" de Donald Judd, les scansions répétitives de Carl Andre, la géométrie essentialiste et kaléidoscopique de Robert Smithson, notamment dans son lien au paysage, ou encore les emboîtements modulaires de Charlotte Posenenske.

Renouant avec Malevitch, Rodtchenko, Gabo, Tatline, Brancusi ou encore Moholy-Nagy, Sobrino privilégie rapidement, dès 1959, les matériaux usinés, dont il perturbe la stabilité et la simplicité initiales dans des jeux de transparence, de reflet et d’opacité. L’artiste utilise ainsi fréquemment, dans ses sculptures et reliefs, ce substitut moderne au verre, par ailleurs précocement utilisé par Moholy-Nagy, qu’est le Plexiglas. Il découvre précisément ce matériau industriel lors d’une visite de l’atelier de Georges Vantongerloo en 1959 et s’en procure au Bazar de l’Hôtel de Ville, par plaques carrées ou rectangulaires, toujours teintes dans la masse, qu’il découpe ensuite en carrés ou en cercles, et qu’il emboîte de façon à faire du matériau lui-même la structure portante de l’œuvre. L’art de Sobrino est en réalité difficile à catégoriser : à la fois concret et perceptuel, cinétique et minimaliste, il se sera détaché de la narration afin d’atteindre le plus parfait silence, la plus parfaite immédiateté de la vibration sensorielle. Un principe commun de réduction et d’accélération y est à l’œuvre : en dépouillant la statuaire moderne de toute narration et de tout décorum, Francisco Sobrino aura plongé ses structures essentialistes dans le flux corrosif et révélateur de l’espace et du temps réels.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

CURATOR: MATTHIEU POIRIER

Galerie Mitterrand is pleased to present a retrospective of Spanish artist Francisco Sobrino in both spaces of the gallery. This exhibition entitled Modus Operandi and that will take place from May 5th to July 8th, 2017 is curated by Matthieu Poirier. In 2015, a Museum Francisco Sobrino was inaugurated in Guadalajara (Spain), where the artist is originally from.

Text by Matthieu Poirier:

Francisco Sobrino (1932-2014) was an iconic representative of Kinetic art, particularly through his involvement with the Group for Research in Visual Art (G.R.A.V.), of which he was one of the founding members in Paris in 1960. As early as 1958, he developed a radical, systematic and minimalist modus operandi which took its inspiration as much from the historic avant-garde movements—Constructivism, Bauhaus, Dada, Neo-plasticism—as it did from the cognitive sciences—the psychology of form, information theory, phenomenology of perception, etc. His visual vocabulary therefore was reduced to the ‘good forms’, that is to say, to the simplest ones, those that are the most immediately accessible to the spectator’s perceptual grasp, limited to a handful of values, most often the primaries, and indeed, a single one at a time, leaning towards monochrome, and the appearance of the raw materials which he uses as a solid or unified whole, devoid of all traces of manual creation. Sobrino pursued this work up until 1968 along with his peers from the G.R.A.V. Movement—Julio Le Parc, Joël Stein, François Morellet, Horacio Garcia-Rossi and Yvaral—and sought to reject the passivity of the work of art and abstract composition, typical of both lyrical and informal movements, as well as concrete art—celebrated at the Salon des Réalités nouvelles (Salon of New Realities)—or the type of art practised by Auguste Herbin or Max Bill.

Sobrino’s clear intention was to reform abstract art, on the basis that if even if its composition were ‘energetic’, the painting or sculpture would still ultimately remain an inert or soothing object, on both a sensory and spatial level. Thus, whether paintings or sculpture, Sobrino’s work can be said to have a strikingly complex appearance in space and time, a quality that is strictly ‘relational’, given the extent to which these open, participative and even penetrable structures resonate with their immediate environment, constructed or human. In addition to the kaleidoscopic and rhythmic structures for which the artist is best known, some of his twisted helical forms are surprising: they endow Sobrino’s incredibly minimalist lines with a baroque consonance, evoking the famous twisted columns supporting the baldachin created by Bernini for Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Nevertheless, whatever their level of visual complexity, Sobrino’s works always arise from basic procedures, involving rotation, inversion, sequencing, grids, swinging and other articulations, which are used as a substitute for all kinds of traditional structures or organization.

This rigorous anti-pictorial, even anti-artistic logic, associated with ZERO and Nouvelle Tendance (New Tendencies) Movements foreshadows numerous realizations associated with North American Minimalism, for example the post-painterly works depicting linear structures by Frank Stella, the parallelepipeds developed in space by Robert Morris, the industrial and slightly ‘unreal’ stamp of Donald Judd, the repetitive scansions of Carl Andre, the essentialist and kaleidoscopic geometry of Robert Smithson, particularly in his relationship to landscape, or the interlocking modular structures of Charlotte Posenenske.

Similar to Malevich, Rodchenko, Gabo, Tatlin, Brancusi and Moholy-Nagy, as early as 1959, Sobrino privileged industrially made materials, whose stability and initial simplicity he disturbed by experimenting with transparency, reflections and opacity. In both his sculptures and reliefs, the artist frequently made use of the modern substitute for glass—Plexiglas—which had already been appropriated by Moholy-Nagy. Sobrino had discovered this industrial material during a visit to Georges Vantongerloo’s studio in 1959 and purchased rectangular and square sections of colour-impregnated Plexiglas at the Bazar de l’Hôtel de Ville department store, which he would then cut into smaller squares or circles, and pile on top of each other in such a way that the material itself became the supporting structure of the artwork. Sobrino’s art is difficult to categorize: both concrete and perceptual, kinetic and minimalist, it is at a distance from narration so as to achieve the most perfect silence, the most perfect immediacy of sensorial vibration. A shared principle of reduction and acceleration is at work here: by stripping the statue of all narrative elements and decorum, Francisco Sobrino plunges his essentialist structures into the both corrosive and revelatory flux of real space and time.